Updated: 04/03/2019

Libyan rebel commander Khalifa Haftar launched an offensive in early April to seize control of Libya’s capital Tripoli, where the internationally recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) of his political rival, Fayez al-Sarraj, is based. Since then, the United Nations Security Council has struggled to maintain a fragile ceasefire in the country, which descended into chaos after the overthrow of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

A little more than two months into the campaign, Haftar’s self-described Libyan National Army (LNA) was defeated in the city of Gharyan just southwest of Tripoli on June 26, leaving the country at a stalemate. Meanwhile, the country’s rival leaders have both accused each other of accepting foreign military support.

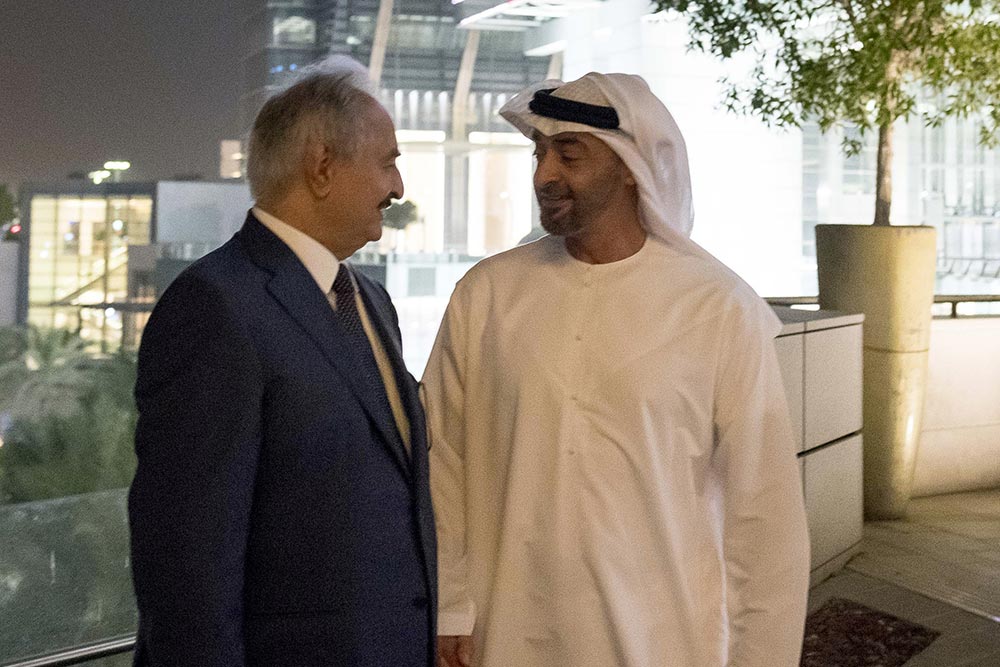

Born in 1943, Haftar served as an officer in the Libyan army for nearly two decades, during which time he trained in the former Soviet Union. After falling afoul of Gaddafi in the late 1980s, he left the military and moved to the United States, where he lived in exile for many years. He returned to Libya in 2011, settling in the eastern city of Benghazi. He has since sought to cast himself as the only leader able to eliminate the threat posed by Islamists, touting his success at fending off militants in the country’s east and south. His actions in Libya have not gone unnoticed abroad: France, Russia, Egypt and, more recently, the United States have all voiced their support for Haftar.

Al-Sarraj, meanwhile, has the backing of Qatar and Turkey as well as the United Nations.

Translator: Rachel Holman

Photos: AFP - Reuters

Copy editors: Cassandre Toussaint, Ratiba Hamzaoui (French)

Design, graphics and development: Studio graphique, France Médias Monde

Editor-in-chief: Ghassan Basile

Senior Producers: Nabil Aouadi, Vanessa Burggraf

All rights reserved © July 2019